25-year-old stroke survivor works to regain the language he lost

Georgia man re-learning speech after having stroke at 25 years old

Piedmont doctors worked to relieve a blood clot in the 25-year-old's brain after he had a stroke. A speech pathologist is working with him get back to speaking without help.

ATLANTA - Bridger White is working hard to find the words he lost when he had a stroke March 12, 2022, at the age of 25.

For now, his mom Angela White is doing the talking for her son, which, she says, is not like Bridger.

"He's outgoing," White says. "He likes to talk. He likes to debate with his dad."

MORE FOX MEDICAL TEAM HEADLINES

Doctors do not know why White, who has no underlying health conditions and was active and physically fit, had the stroke that landed him at Shepherd Pathways, Shepherd Center's outpatient clinic in Decatur.

That day of the stroke, he and his dad were in Jasper, loading lumber they had just bought onto the back of their pickup truck.

BASEBALL HELPS GEORGIA BOY PUSH THROUGH CANCER CURVEBALL

"When his dad went to throw the strap across the truck to tie the lumber down, he said Bridger didn't know what to do with it, and he kind of slumped," Angela White says. "When his dad went over there, Bridger couldn't talk. He knew the signs, and he immediately called 911."

With White at Piedmont Mountainside Hospital, neurosurgeon Mike Stiefel, medical director of Piedmont Atlanta's Comprehensive Stroke Center, began getting messages on his phone at home.

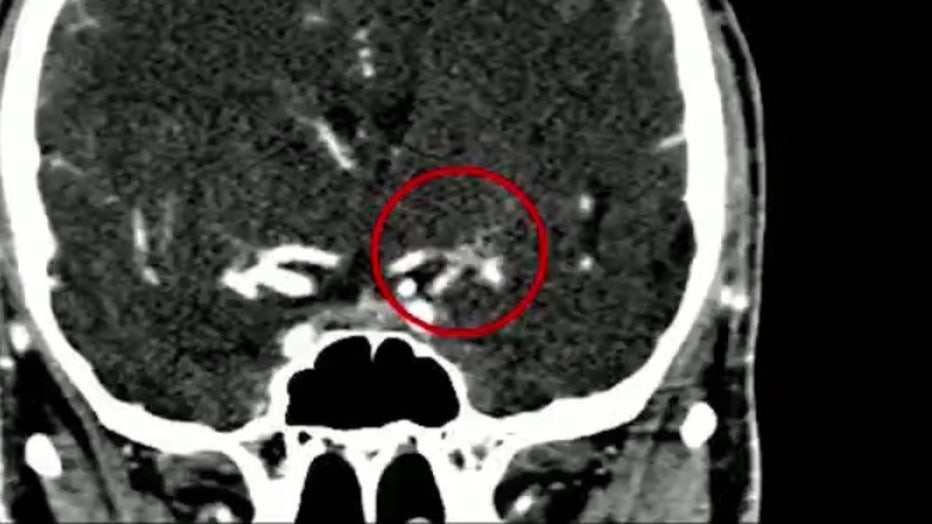

"The first texting that I saw was the ER doctor texting that this was a 25-year-old gentleman who came in with an acute stroke and couldn't talk," Dr. Stiefel remembers. "The next thing we see are the stroke images,"

They did not look good.

Images of a 25-year-old Georgia man's brain from Piedmont Atlanta's Comprehensive Stroke Center.

"He had a large area of brain that was very vulnerable," Dr. Stiefel says. "So, it tells us that, if we restore the blood flow, there is a chance that we could reduce the amount of damage. However, if we don't restore blood flow, everything that was vulnerable usually goes on to be permanently damaged."

The clot was blocking blood flow to an area on the left side of White's brain.

"Your left side of the brain controls movement on your right side, and it controls speech," Dr. Stiefel says. "The same stroke on the right side would not have affected his speech."

White was given an IV drug to try to stop the stroke, then he was rushed by ambulance to Piedmont Atlanta, 60 miles away.

Within 4 and a half hours of his first symptoms, White was in surgery.

"In stroke we have a saying: time is brain," Stiefel says.

At Piedmont Atlanta, Dr. Stiefel and his team performed a mechanical thrombectomy, threading a catheter, or a thin hollow tube, through an incision in White's groin up to the clot in his brain, where they pushed a tiny device known as a stent retriever across the clot.

"What it does, is, it helps push the clot into the device, and we leave it in there for anywhere from 1 to 3 minutes," Stiefel says. "Then, under suction, we pull that device out."

It took 2 or 3 tries to remove the clot and restore the blood flow.

A month later, White is physically back to normal, but he is still trying to recover his ability to speak, write and read.

He has been diagnosed with aphasia, a communication disorder caused by the damage to the area of his brain where he had the stroke.

White began his stroke rehabilitation therapy at Shepherd Center at the end of March.

"We see stroke improvement 12 to 18 months out," Dr. Stiefel says. "So, where he is today is definitely not where he is going to be 6 months from now or 12 months from now."

At Shepherd Pathways, speech-language pathologist Breanna Desousa Miranda is teaching White techniques to cue his brain and help him find the right word.

"Oftentimes, with aphasia, we have the word in our brain, we have a picture of the word," Desousa Miranda says. "So, what we're doing is trying to access that word by using these description techniques."

For close to an hour, they run through prompts, as Desousa Miranda tries to help White retrieve the correct word or sentence automatically, as she asks him a series of questions that might come up in conversation.

"With aphasia, you see how intellectual intact people are, that it really just is they're locked in," she says. "So, how do we pull it out?

"So, essentially, what you're doing, is you're trying to repeat, repeat, repeat. So, these things become involuntary, so that he's able to do it without thinking about it, just like he would say, 'One, two, three.'"

White uses a melody Desousa Miranda has taught him to say his name.

"A lot of times, you have the ability to sing something, but then it's hard to just say it," she says. "So, he knows the song, and he's cueing himself."

A month ago, Angela White says her son could only speak a few words.

"Seeing where he was to where he is today is just amazing to me," she says.

Bridger White's dream is to one day go back to work, and regain his independence.

For now, he is taking things one day at a time, and one word at a time.

"He's determined," his mother says. "He wants to get back to the Bridger that we know."