This document can help you call the shots, if you become critically ill

ATLANTA - None of us likes to think about what would happen if we became seriously ill or were facing the end of our lives.

Would we want doctors to perform CPR if our heart stops?

Are we comfortable with the idea of being placed on a ventilator, if we cannot breathe on our own?

Do we want to be placed on a feeding tube, if we can no longer eat?

Northside Hospital palliative care specialist Dr. Huda Sayed says those are all important questions to think about now, while we are still healthy and can make decisions about the future.

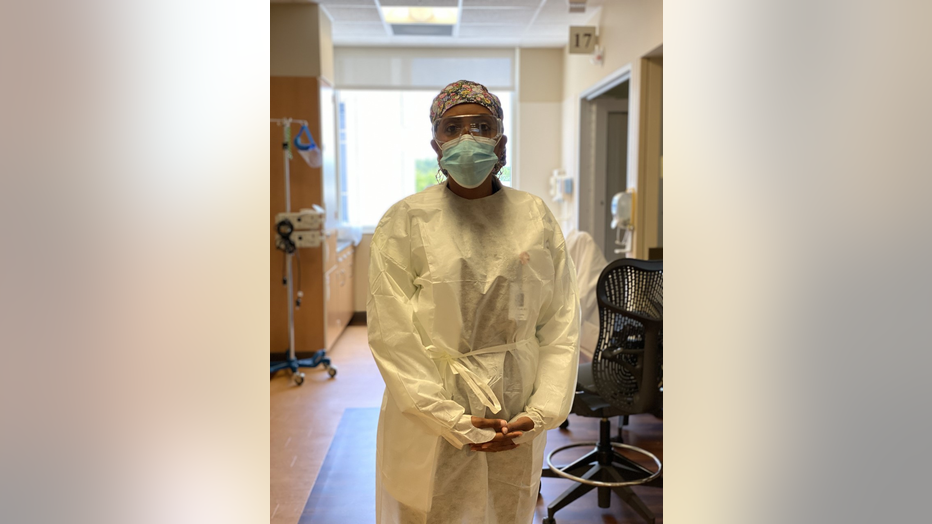

Dr. Huda Sayed, a Northside palliative care physician, stands in the COVID-19 unit where she works. (Dr. Huda Sayed)

Dr. Sayed has spent the last few months working in a COVID-19 ICU, with patients who never imagined they would end up in a critical care unit, some on a ventilator.

"There are so many things we can do for patients," Sayed says. "We live in a country where we have amazing technology. But, sometimes, we really have to be careful. Are we doing it for the patient, or are we doing it to the patient?"

To better direct your medical care, Sayed says, start thinking about what you want and don’t want should you become ill or incapacitated.

Next, she says, create an advance directive, a document that spells out in writing what kind of treatment you want.

As part of the document, Sayed says, you can choose a health care proxy, or even two, to make medical decisions for you if you cannot speak for yourself.

Your proxies should be people you trust, who share your views and values and will follow your directions.

Have a discussion with them to make sure they are comfortable being your proxy before appointing them as your medical stand-ins.

You can find the advance directive forms free online.

"You don't need a lawyer," Sayed says. "It doesn't need to be notarized. All you need are two witnesses that are not the two patients (proxies) you chose. By doing so, now you have a written document."

Too often, Dr. Sayed says, families are left to make difficult end-of-life decisions, without knowing what their loved one would want because they've never talked about it.

Making your wishes clear, she says, would free your loved ones from that burden.

"Yes, it's not a great topic to talk about," she says. "But, you do it once. You talk to your family. You tell them what your wishes are. Be as specific as you can be, because that's the most important thing. Then, you put it away."

Once you have signed your advance directive, give a copy of it to your health care proxies and your doctor.

Keep an extra copy to give to your medical team, should you ever need to be hospitalized.

Lastly, remember to update your advance directive every few years, or if your medical situation changes.

To read more about creating an advance directive, visit https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/advance-care-planning-healthcare-directives