Biden to meet Putin face-to-face for Geneva summit in June

WASHINGTON - President Joe Biden will hold a summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin next month in Geneva, a face-to-face meeting between the two leaders that comes amid escalating tensions between the U.S. and Russia in the first months of the Biden administration.

The White House confirmed details of the summit on Tuesday. The two leaders' meeting, set for June 16, is being tacked on to the end of Biden's first international trip as president next month when he visits Britain for a meeting of Group of Seven leaders and Brussels for the NATO summit.

"The leaders will discuss the full range of pressing issues, as we seek to restore predictability and stability to the U.S.-Russia relationship," White House press secretary Jen Psaki said in a statement announcing the summit.

Biden first proposed a summit in a call with Putin in April as his administration prepared to levy sanctions against Russian officials for the second time during the first three months of his presidency.

Russia's President Vladimir Putin attends the online Leaders Summit on Climate hosted by U.S. President Joe Biden on April 22, 2021 in Moscow, Russia. (Photo by Alexei DruzhininTASS via Getty Images)

White House officials said earlier this week that they were ironing out details for the summit. National security adviser Jake Sullivan discussed details of the meeting when he met with his Russian counterpart, Nikolay Patrushev.

The Kremlin, in is own statement announcing the meeting, said that the presidents will discuss "the current state and prospects of the Russian-U.S. relations, strategic stability issues and the acute problems on the international agenda, including interaction in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic and settlement of regional conflicts."

The White House has repeatedly said it is seeking a "stable and predictable" relationship with the Russians, while also calling out Putin on allegations that the Russians interfered in last year's U.S. presidential election and that the Kremlin was behind a hacking campaign — commonly referred to as the SolarWinds breach — in which Russian hackers infected widely used software with malicious code, enabling them to access the networks of at least nine U.S. agencies.

The Biden administration has also criticized Russia for the arrest and jailing of opposition leader Alexei Navalny and publicly acknowledged that it has low to moderate confidence that Russian agents were offering bounties to the Taliban to attack U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

The Biden administration announced sanctions in March against several mid-level and senior Russian officials, along with more than a dozen businesses and other entities, over a nearly fatal nerve-agent attack on Navalny in August 2020 and his subsequent jailing. Navlany returned to Russia days before Biden's Jan. 20 inauguration and was quickly arrested.

Last month, the administration announced it was expelling 10 Russian diplomats and sanctioning dozens of Russian companies and individuals in response to the SolarWinds hack and election interference allegations.

But even as Biden moved forward with the latest round of sanctions, he acknowledged that he held back on taking tougher action — an attempt to send the message to Putin that he still held hope that the U.S. and Russia could come to an understanding for the rules of the game in their adversarial relationship.

In fact, he brought up the idea of holding a third-country summit in an April 13 call in which he notified Putin that the second round of sanctions was coming.

During his campaign for the White House, Biden described Russia as the "biggest threat" to U.S. security and alliances, and he disparaged his predecessor, President Donald Trump, for his cozy relationship with Putin.

Trump avoided direct confrontation with Putin and often sought to downplay the Russian leader’s malign actions. Their sole summit, held in July 2018 in Helsinki, was marked by Trump’s refusal to side with U.S. intelligence agencies over Putin’s denials of Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Weeks into his presidency, Biden said in an address before State Department employees that he told Putin in their first call that he would be taking a radically different approach to Russia than Trump.

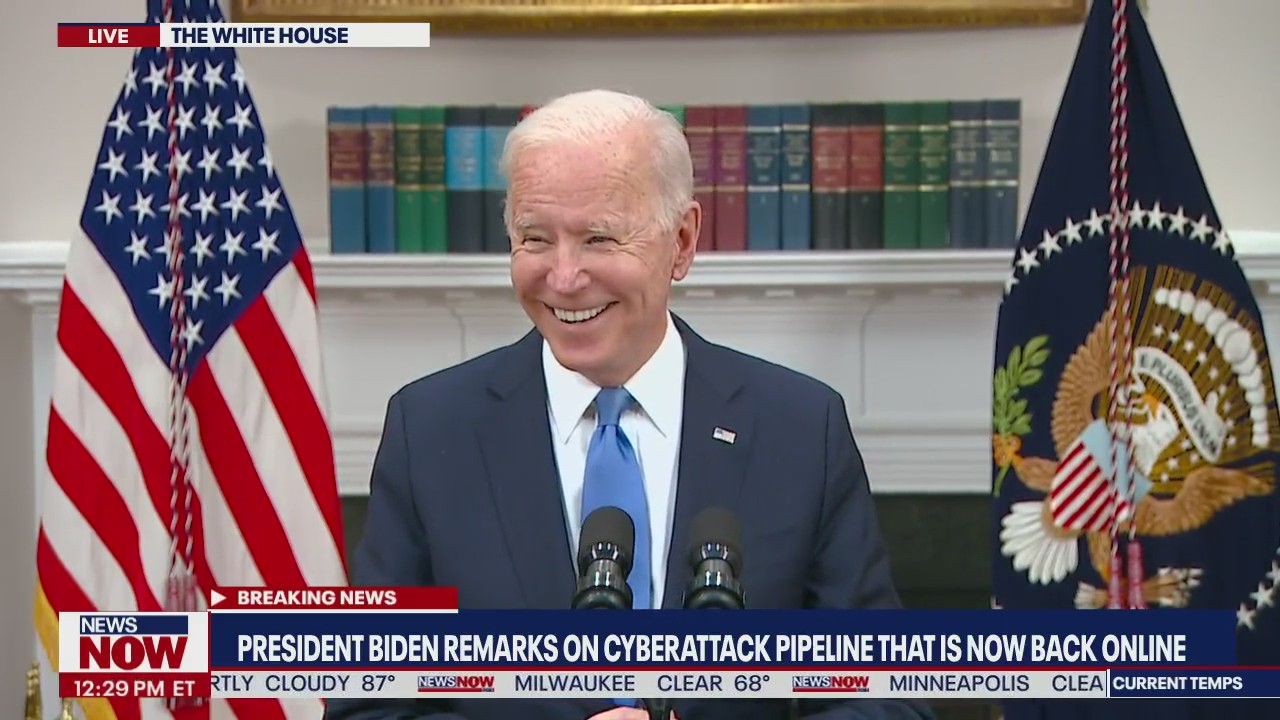

"I made it clear to President Putin, in a manner very different from my predecessor, that the days of the United States rolling over in the face of Russia’s aggressive actions — interfering with our election, cyber-attacks, poisoning its citizens — are over," said Biden, who last week spoke to Putin in what White House officials called a tense first exchange. "We will not hesitate to raise the cost on Russia and defend our vital interests and our people."

In March, Biden in an ABC News interview responded affirmatively when asked by interviewer George Stephanopoulos whether he thought Putin was "a killer."

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that Biden's comment demonstrated he "definitely does not want to improve relations" with Russia and that relations between the countries were "very bad."

Geneva, a rich, if mid-size, city on the banks of Lake Geneva, offers bucolic vistas of the Mont Blanc peak — the highest in Western Europe — and a reputation as both a hub for international institutions and an icon of Switzerland’s much ballyhooed neutrality.

Geneva became a leading crossroads of diplomacy in the postwar years of Cold War intrigue, an intersection where the Soviet-dominated Eastern bloc met the American-styled capitalist West.

The city last hosted American and Russian leaders in 1985, when President Ronald Reagan met Mikhail Gorbachev -- a summit considered short on substance but critical in breaking the ice between East and West and fostering what would become mostly friendly relations between the two men through their tenures.

A Biden-Putin meeting there could revive the reputation of the city as a hub for international diplomacy, a far cry from the Trump administration, which largely shunned its globalist institutions like the World Trade Organization and the World Health Organization. Biden’s administration has re-engaged with both of those organizations.

___

Keaten reported from Geneva. Associated Press writer Matthew Lee contributed reporting.