Transcript: National Prescription Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit in Atlanta

ATLANTA - The White House has released the full transcript from the discussion panel President Obama took part in on Tuesday afternoon as part of the National Prescription Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit in Atlanta.

App users: Click here to watch President Obama's full summit discussion

The transcript is as follows:

REMARKS BY THE PRESIDENT IN PANEL DISCUSSION AT NATIONAL PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE AND HEROIN SUMMIT

AmericasMart Building Two

Atlanta, Georgia

2:27 P.M. EDT

DR. GUPTA: Mr. President, I'm going to start with you. Obviously you have a lot going on, and this is a significant commitment. You flew down here. You're attending this conference. You're going to make comments here. Why this particular topic for you, sir?

THE PRESIDENT: Because it's important, and it's costing lives, and it's devastating communities.

And I want to begin by thanking Congressman Rogers for helping to put this together and the leadership that he has shown. We very much appreciate him and his staff for making this happen. (Applause.) I want to thank UNITE, and the organization that has been carrying the laboring oar on this issue for many years now. We are very grateful to them. And I just want to thank our panelists -- especially Crystal and Justin. Obviously we greatly appreciate the work the doctor does, but part of what's so important is being able to tell in very personal terms what this means to families and to communities. And so I am looking forward to hearing from them.

This is something that has been a top priority of ours for quite some time. My job is to promote the safety, the health, the prosperity of the American people. And that encompasses a whole range of things. It means that we're tracking down ISIL leaders, and it means that we're responding to natural disasters, and it means that we're trying to promote a strong economy. And when you look at the staggering statistics in terms of lives lost, productivity impacted, costs to communities, but most importantly, cost to families from this epidemic of opioids abuse, it has to be something that is right up there at the top of our radar screen.

You mentioned the number 28,000. I's important to recognize that today we are seeing more people killed because of opioid overdose than traffic accidents. I mean, think about that. A lot of people tragically die of car accidents, and we spend a lot of time and a lot of resources to reduce those fatalities. And the good news is, is that we've actually been very successful. Traffic fatalities are much lower today than they were when I was a kid because we systematically looked at the data and we looked at the science, and we developed strategies and public education that allowed us to be safer drivers.

The problem is here we've got the trajectory going in the opposite direction. So in 2014, which is the last year that we have accurate data for, you see an enormous ongoing spike in the number of people who are using opioids in ways that are unhealthy, and you're seeing a significant rise in the number of people who are being killed.

And I had a town hall in West Virginia where -- I don't think the people involved would mind me saying this because they're very open with their stories -- the child of the mayor of Charleston, the child of the minority leader in the House in West Virginia, a former state senator -- all of them had been impacted by opioid abuse. And it gave you a sense that this is not something that's just restricted to a small set of communities. This is affecting everybody -- young, old, men, women, children, rural, urban, suburban.

And the good news is that because it's having an impact on so many people, as Hal said, we're seeing a bipartisan interest in addressing this problem -- not just taking a one-size-fits-all approach, not just thinking in terms of criminalization and incarceration -- which, unfortunately, too often has been the response that we have to a disease of addiction -- but rather, we've got an all-hands-on-deck-approach increasingly that says we've got to stop those who are trafficking and preying on people, but we also have to make sure that our medical community, that our scientific community, that individuals -- all of us are working together in order to address this problem.

And I'm very optimistic that we can solve it. We're seeing action in Congress that has moved the ball forward. My administration, without congressional action, has taken a number of steps. And I know that you've heard from some of our administration here today about, for example, providing $100 million to community health centers so that people have more access to treatment. (Applause.)

Concentrating on physician education in terms of how they prescribe painkillers to prevent abuse. Making sure that the treatment -- Medication-Assisted Treatment programs are more widely available to more people. Making sure that the -- not antidote, but at least means of preventing people once they have overdosed from actually dying is being carried by EMTs. So we're taking a number of steps. But, frankly, we're still under-resourced.

I think the public doesn't fully appreciate yet the scope of the problem. And my hope is, is that by being here today, hearing from people who have gone through heroic struggles with this issue, hearing from the medical community about what they're seeing, that we've got the opportunity to really make a dent on this. And I just want to thank all the people who are involved here today, because I know we've got people who are much more knowledgeable and are doing great work out in the field each and every day. My hope is, is that when I show up, usually the cameras do, too, and it helps to provide us a greater spotlight for how we can work together to solve this problem. (Applause.)

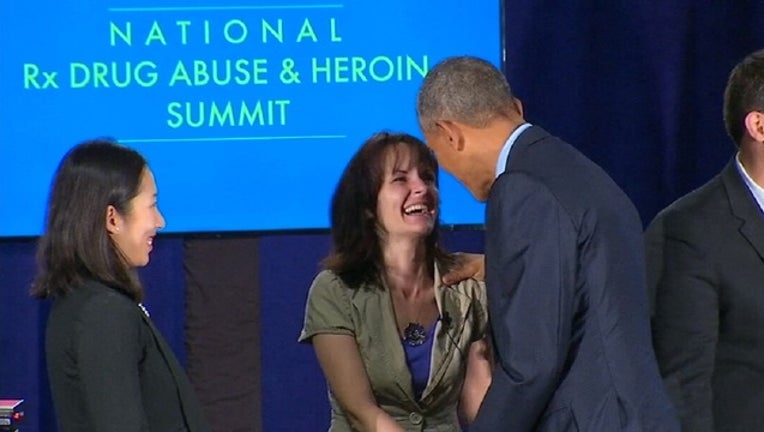

DR. GUPTA: Thank you very much. Mr. President, you had a chance to hear a little about Crystal Oertle’s story backstage -- again, 35 years old, mother of two.

First of all, are you comfortable talking about your story? Is this something you’re comfortable with?

MS. OERTLE: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: My understanding is, around age 20, you started using Vicodin recreationally, once a week or so. Wonder if you could tell me what sort of happened at that stage in your life? How did things progress from there on?

MS. OERTLE: Well, I think my path into addiction, which eventually was heroin addiction, is pretty similar to a lot of people’s stories. They start out with the Vicodin, low milligrams, not knowing how addictive it can be, using it recreationally until then they need it. That’s what happened with me. It slowly happened from weekend to then needing it throughout the week, needing something to go to work. Eventually I needed something stronger than the Vicodin. I was doing OxyContins, Dilaudid, things like that, until that eventually led into me doing heroin.

DR. GUPTA: Can you talk about that? When you say it eventually led to heroin, what does that mean?

MS. OERTLE: Well, I was physically addicted. And the higher milligram things like Oxycontin and Dilaudid to me are pretty much like heroin. They’re like synthetic heroin -- almost as strong. So when it came to the point and I couldn’t find those kinds of pills, I had to go to the street to prevent my withdrawal symptoms, so that I could participate in my life -- my children, getting them to school, me going to work. So that’s how I got into using heroin after the pills.

DR. GUPTA: Again, you have two children.

MS. OERTLE: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: And you were doing this in order to be able to function, it sounds like. So heroin -- where were you using it?

MS. OERTLE: In my home. In the bathroom -- while my kids were there, while they were at school. It was so much a part of my life -- it was a part of my life. It’s crazy to think about now the things that I did, but it was necessary, or I wouldn’t have been able to function.

DR. GUPTA: Who do you call, if you will? What did you do when you started to get help? How did you -- where did you even begin?

MS. OERTLE: Well, I tried a few times on my own. It didn’t work. I personally couldn’t get through the withdrawal symptoms. I couldn’t tough it out. I know some people can. I couldn’t do it. This last time has been the most successful recovery for me. I’ve been in recovery about a year. (applause.) Thank you.

I’m on it’s called Medicated-Assisted Treatment, and I take Suboxone, which is the Buprenorphine that the Surgeon General was talking about earlier. I’m in a program, it’s called UMADAOP -- it stands for Urban Minorities Alcohol and Abuse Outreach Program -- I think that’s what it stands for.

THE PRESIDENT: That’s pretty good. (Laughter.)

MS. OERTLE: And that’s where I go. And it’s very intense. It’s a lot of counseling, group counseling with other people that are in treatment, and then individual counseling, talking to a doctor. It’s just really good. It’s really worked for me this time.

DR. GUPTA: And again, I prefaced by saying talk about what you’re comfortable talking about, but did you have interaction with law enforcement?

MS. OERTLE: Yes, yes, quite a few times.

DR. GUPTA: What happened?

MS. OERTLE: I’ve had to steal. I’ve stolen from department stores and -- to feed my habit. I’ve been involved in drug busts a couple times. So, yeah.

DR. GUPTA: When you talk about this medically assisted therapy, you’re essentially using one type of medication -- doesn’t give you the same type of euphoria or high -- but to help you wean off of the heroin in this case. Is that right?

MS. OERTLE: Yes, yes. And what I take actually blocks -- I couldn’t get high if I wanted to use heroin. It blocks the receptors in the brain so that you can’t get high.

DR. GUPTA: And I’m going to come back to you in a few minutes again, but I wonder if you could just say -- you’ve tried this a bunch of times, and now you’ve been a year again in recovery. Is there something that worked this time? And for people out there who say it just doesn’t work for me, I’ve tried, it doesn’t work -- what worked this time for you?

MS. OERTLE: I think this time I wanted it more than anything, and taking that step forward, along with the support that I get from my family and UMADAOP advocating -- I mean, this helps. Getting out there, telling my story, and helping other people helps me, and it makes me want to stay in recovery and keep doing what I’m doing.

DR. GUPTA: Great. Thank you very much.

MS. OERTLE: Thank you. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: Doctor Wen, you’re sort of at the front line of this. You and I had dinner a few months ago, and I mean some of the stories you shared were pretty remarkable. You’re an ER doctor. How did you get into this? Why is this issue so important for you?

DR. WEN: Actually a very similar story to Crystal’s. I saw a patient who I got to know over the course of her getting treated in the ER. And when you know someone very well as an ER doctor, you know there’s something wrong. But this woman was in her late 20s. She was a competitive swimmer. She tore disks in her back and started out with prescription pain pills, but then got addicted to them, and then switched to heroin. And this was a woman who was in a downward spiral. And she recognized -- she was losing her job; she was about to lose her kids; she was homeless.

And she came to us basically every week in the ER. And she knew that she needed help. I mean, this was someone who came to us every week saying, I want help for my addiction. And it’s one of the worst realizations as a doctor. It's one of the most humbling things and the worst feelings as a doctor to know that you can't help them; that what this patient needed, what so many of our patients need is treatment -- addiction treatment at the time that they're requesting it. But we couldn't get it. (Applause.)

I mean, we would never say that to someone who has a heart attack. We would never say, go home, and if you haven't died in three weeks, come back and get treated. (Laughter and applause.)

So that's what we faced. And I remember that I talked to her this one time about getting into treatment -- she really wanted to do it. We set her up with an appointment, but it wasn't until two weeks later. And she went home that day and overdosed, and came back to us in the Europe. We tried to resuscitate her, but we couldn't save her.

And I think about her all the time because she had come to us so many times requesting treatment. And, yes, clearly, there is a difference between how we treat her and how we treat everybody else because we need to recognize that addiction is a disease. If we treat addiction like a crime then we're doing something that's not scientific, that's inhuman, and it's, frankly, ineffective. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: Mr. President, you've heard these sorts of stories before. When you hear it so lucid in terms of what the situation was like in the emergency room, the woman wanted help, what is your reaction when you hear this story?

THE PRESIDENT: It's heartbreaking. And the fact is that for too long, we have viewed the problem of drug abuse generally in our society through the lens of the criminal justice system.

Now, we are putting enormous resources into drug interdiction. When it comes to heroin that is being shipped in from the south, we are working very aggressively with the Mexican government to prevent an influx of more and more heroin. (Applause.) We are now seeing synthetic opioids that are oftentimes coming in from China through Mexico into the United States. We're having to move very aggressively there, as well.

So the DEA -- (applause) -- our law enforcement officials -- (laughter) -- good job, DEA. (Laughter and applause.) We're staying on cutting off the pathways for these drugs coming in. But what we have to recognize is, in this global economy of ours that the most important thing we can do is to reduce demand for drugs. And the only way that we reduce demand is if we're providing treatment and thinking about this as a public health problem, and not just a criminal problem. (Applause.)

Now, this is a shift that began very early on in my administration. And there's a reason why my drug czar is somebody who came not from the criminal justice side but came really from the treatment side -- and himself has been in recovery for decades now. (Applause.) Because this is something that I think we understood fairly early on.

Now, I'm going to be blunt -- I hope people don't mind. I was saying in a speech yesterday, your last year in office, you just get a little loose. (Laughter.) But I said this in West Virginia as well, and I think we have to be honest about this -- Part of what has made it previously difficult to emphasize treatment over the criminal justice system has to do with the fact that the populations affected in the past were viewed as, or stereotypically identified as poor, minority, and as a consequence, the thinking was it is often a character flaw in those individuals who live in those communities, and it's not our problem they're just being locked up. (Applause.)

And I think that one of the things that's changed in this opioid debate is a recognition that this reaches everybody. So there's a real opportunity -- not to reduce our aggressiveness when it comes to the drug cartels who are trying to poison our families and our kids -- we have to stay on them and be just as tough -- but a recognition that, in the same way that we reduce tobacco consumption -- and I say that as an ex-smoker -- (applause) -- in the same way that, as I mentioned earlier, we greatly reduced traffic fatalities because we applied a public health approach, so that my daughter's generation understands very clearly you don't drive when you're drunk, you put on your seatbelt, and we also then instituted requirements for things like seatbelts and airbags and reengineered roads, all designed to reduce fatalities -- if we take the same approach here, it can make a difference.

So when I'm listening to Crystal and I'm thinking, what a powerful story, I want to make sure that for all the other Crystals out there who are ready to make a change that they're not waiting for three months or six months in order to be able to access treatment. (Applause.)

Because, Crystal, I think you'd agree that if all we were doing was dispensing the drug that is blocking your cravings for an opioid but you weren't also in counseling and working with families, et cetera, it's shown that it doesn't work as well.

We've got to make sure that in every county across America, that's available. And the problem we have right now is that treatment is greatly underfunded. (Applause.) And it's particularly underfunded in a lot of rural areas. Our task force, when we were looking at it, figured out that in about 85 percent of counties in America, there are just a handful or no mental health and drug treatment facilities that are easily accessible for the populations there. So if you get a situation in which somebody is in pain initially because of a disk problem, they may not have health insurance because maybe the governor didn't expand Medicaid like they should have under the ACA -- (applause) -- they go to a doctor one time when the pain gets too bad, the doctor is prescribing painkillers, they run out, and it turns out it's cheaper to get heroin on the street than it is to try to figure out how to refill that prescription, you've got a problem.

And that's why, for all the good work that Congress is doing, it's not enough just to provide the architecture and the structure for more treatment. There has to be actual funding for the treatment. And we have proposed in our budget an additional billion dollars for drug treatment programs in counties all across the country. And my hope is, is that all the advocates and folks and families who are here and those who are listening say to Congress, this is a priority. We've got to make sure that incredibly talented young people like Crystal are in a position where they can get the treatment when they need it. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: Justin, you're 28 years-old, and this, for you, started at a very young age. I mean, you're still young, but this started at a very young age. Can you share with us a little bit of -- when was the first time you started taking some of these drugs?

MR. RILEY: So I really started experimenting with kind of

-- the way that I frame it, as a kind of a hole in the soul. I never felt good enough or liked who I was or how I sounded or anything of that nature. And being kind of just in my own skin was something very, very uncomfortable for me. And that started around 3rd, 4th grade, where I was consciously very disappointed with who I was.

And for those of you who have ever been a 3rd-grader or know a 3rd-grader, that's a sad statement. That the future of our country -- at such a young age, it's so sad and hopeless. But the other side of that, though, and where we really come into play -- and I'll start to sound a little bit like a broken record -- and if you don't mind, sir, I'll take a leaf out of your book of being blunt, but even more important than when that started, how that started, what that looked like -- even though that's important to understand -- is that people can and do recover. (Applause.) And there are millions -- there are millions and millions and millions of people that can and do recover.

I am very fortunate to be able to be up here and to represent, and to be an example. I am not special or unique. I have worked very hard, and I can appreciate that, and I would challenge others to also work hard. But those of us who are in recovery and know people that can and do recover, that's -- and even to me -- as important as this part of the conversation is. And we have to have this part -- is what's even less talked about and even more underfunded is that people can and do recover, and they do that in a lot of different ways, and they're extraordinary. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: To the extent that you're comfortable, again -- did you say 3rd grade?

MR. RILEY: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: When you say 3rd grade, I mean, were you starting to use these sorts of drugs? That's, what, seven, eight, nine years-old?

MR. RILEY: So I had -- my mom is close, in the third row, so that's cool. Hi, mom. (Laughter.) So I had a precarious allergy and still do -- I was allergic to poultry. And so I learned at a young age, you take Benadryl, and Benadryl then makes you sleepy. And then if you also know you don't want to deal with life, just sleep through it. So for me -- and they didn't fly me in because I'm the Benadryl guy, but that was part of my early journey. But that stopped satiating that hole in the soul, and I literally couldn't sleep through all of life, so eventually that did manifest into other things, of course.

DR. GUPTA: So from Benadryl you started using other medications? I mean, you're still pretty young. I mean, if you don't mind me asking, how did you even gain access to some of these other drugs at that age?

MR. RILEY: Very typical -- at least where I grew up, and I grew up in Greeley, Colorado, a great rural community. And amazing parents, amazing family, but it's pretty commonplace to have alcohol and other drugs in the home. My parents raised me exceptionally well, but that feeling of inadequacy, searching for something to fill that space was pretty strong for me.

DR. GUPTA: You eventually were in recovery, and you were in and out of recovery seven times is my understanding.

MR. RILEY: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: Can you tell me about the first time? Did you pursue it on your own? Was your family -- did they help nurture this for you?

MR. RILEY: I think the true first attempt at recovery for me -- which was to no surprise when you have such an amazing family and parents -- was my parents took me to my pediatrician, and they said, Luke -- they call me by my middle name -- Luke is struggling. He's doing the sports thing, doing leadership stuff in school, but we found out that he's been drinking. Instead of water in his Nalgene for tennis practice, there's vodka in there. What are we going to do about that?

And culturally -- which I think speaks to what we brought up earlier and what you articulated so well -- was, culturally speaking, that bias or that lack of understanding that there's got to be something bigger going on here -- before this gets into what we now know today is proportions of an epidemic -- but it was chalked up to boys will be boys. And it was one of those very rare moments when I decided to be open and honest around some of the things that I was doing. But again, having -- and I mean, it's a pediatrician, right? I mean, I'm not a doctor, clearly, but very, very much -- almost without knowledge. I mean, there was just nothing that that doctor at that point in time could do other than, well, you know, he's doing good in sports, doing good in school, I'm sure this good-looking young guy will be okay. And that wasn't the case.

DR. GUPTA: You weren't okay, I mean, clearly, from what you're describing. How bad did things get for you?

MR. RILEY: Bad, to me, is a very relative term. I've met a lot of individuals that went through things that, frankly, I don't know IF I could have gone through. But for me, again, even more so than how bad did it get or how many stories could I go into to articulate the hopelessness or the things that my family went through, is truly the reverse of that -- the recovery, the power of those stories of when I did start to get well. And when I was allowed to be in my parents' home, when my father was the best man in my wedding, when my dad called me when I was a couple years into recovery and he said, because of what you have done, I want to be in recovery. And he's still in recovery to this day. And those stories to me -- (applause.)

THE PRESIDENT: And, Sanjay, maybe I can just interject, because I'm listening to Justin's story, and when I was a kid, I was -- how would I put it? -- Not always as responsible as I am today. (Laughter.) And in many ways I was lucky because, for whatever reason, addiction didn’t get its claws in me, with the exception of cigarettes, which is obviously a major addiction but doesn’t manifest itself in some of the same ways.

But I think that part of Justin’s point is really powerful, which is, we live in a society where we medicate a lot of problems and we self-medicate a lot of problems. And the connection between mental health, drug abuse is powerful. Anxiety, folks who are trying to figure out coping skills -- we have an entire industry that says, we’re going to help you self-medicate. And the line between alcoholism, which is legal, and folks who are taking Vicodin and then on to harder illegal substances isn’t always that sharp, particularly among children.

So one of the conclusions that we came to is that it’s important for our health system to be addressing wellness in a way that prepares doctors, provides resources, insurance policies -- all that can help with these issues, as opposed to, if you have a broken arm you get treatment, but if you’ve got significant depression that you may be masking through alcohol or through opioids, then you’re not getting treatment.

And one of the things that we tried to do through the Affordable Care Act was insist on parity in insurance policies. One of the steps we’re now taking in response to the opioid epidemic is to really ratchet up the guidelines that we’re providing to insurers, so that if that young lady that Leana was talking about comes in, if she has insurance, that, in fact, that it’s treated as a disease and it’s covered. And Medicaid and Medicare start really taking parity seriously so that mental health issues and addiction issues are treated as a disease in the same way that if somebody came in with a serious medical illness that it’s treated. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: So can you give a little bit more detail on that? Because people talk about mental health parity and they say this has been around for some time but the impact has not been felt the way that a lot of people would like to feel it. What will the task force be able to do that hasn’t already been done?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, the goal of the task force is to essentially develop a set of tools, guidelines, mechanisms so that it’s actually enforced, that the concept is not just a phrase -- an empty phrase, but, as a practical matter, if you’re trying to get a provider for treatment, they may or may not get reimbursed, but there’s a consistency in terms of how we approach the problem.

And when it comes to Medicaid and Medicare, obviously there are guidelines, because that’s a government program that we can provide. When it comes to how we oversee the parity provisions in the Affordable Care Act, we’ve got to let the insurance carriers know that we’re serious about this. And this is where, though, the public education and employer education around these issues is very important, as well.

Because 85 percent of folks still get their health insurance through their job, through their employer. And for business owners, for companies to recognize that they are much better off checking and pressing their insurer to see that, in fact, mental health and substance abuse parity does, in fact, exist, they will save money, their workers will be more productive, and they’ll be getting more bang for their insurance buck. That’s all part of the approach that I think we can take and we’ve got to carry through over the next several years.

DR. GUPTA: Thank you.

Crystal, when we spoke earlier, you talked about the fact that you wanted to describe to the President some of what you experienced in the criminal justice system. And I think what you were talking about was some of the stigma you faced. I wonder if you could, again, describe some of your experiences and what that stigma really felt like.

MS. OERTLE: Well, the place where I go for my counseling, I talk to a lot of people that are on probation. And the probation officers don’t treat them like they have a disease and the medication is something that’s treating their disease. They don’t want them to be on it, and they don’t understand. I don’t think they have enough education. It’s great to hear the President say the “disease of addiction.” That’s wonderful. (Applause.) But there still is a stigma. For me, even coming here -- and nobody here treated me bad or anything, but it’s in the back of my mind.

THE PRESIDENT: They better not have. Somebody treats Crystal bad, you’ve got to talk to me. And I’ve got Secret Service, the U.S. Armed Forces. (Laughter.) Don’t mess with her.

MS. OERTLE: But it is in the back of my mind, like, I’m not worthy, to be really honest.

DR. GUPTA: Criminal justice -- parole officers, counselors? I mean, was this --

MS. OERTLE: Yes. Some doctors even. One doctor I went to -- and I talked to some of your people today about the Parity Act. I don’t have a problem with it now. Everything is paid for. I’m on Medicaid. But I have gone to doctors before that would only take cash. And they haven’t been nice. I’ve had a couple really nasty incidences with things that the doctors even said about another patient in treatment, and I just want that --

THE PRESIDENT: That’s discouraging.

MS. OERTLE: Yes, yes.

DR. GUPTA: Doctor Wen?

DR. WEN: What you’re describing is so unfortunate, but it’s so prevalent. When we talk about, for example, Naloxone, the overdose medication, there are people who would question whether giving someone Naloxone will make them more likely to use drugs. But we would never say that about somebody who has a peanut allergy. We wouldn’t say, oh, we’re not going to give you an Epi-Pen, because it might make you eat more peanuts next time. (Applause.)

We see that stigma in Baltimore, where I am. And we’re coming up to now a year post the unrest in our city, and often it’s tempting to look at what happened in our city as what’s in front of us, which is angry young people committing acts of violence. But then if we look just one step deeper, we see what’s resulted in deep poverty and deep disparities from our policies of mass incarceration and mass arrest. (Applause.)

I mean, we have a city -- if we look at the numbers in our city, we have 73,000 arrests made every year in a city of 620,000. And when we look at our individuals who are in our jails, four out of 10 have a diagnosed mental illness; eight out of 10 use illegal substances. So we are criminalizing people without giving them the reentry resources to get their lives back in order. We’re treating addiction differently from any other disease.

DR. GUPTA: You provided your own name as a doctor at all the pharmacies, I understand, in Baltimore, a certain area, so that anybody going in could get their Narcan, their Naloxone, if they wanted. Is that right?

DR. WEN: That’s right. So we issued a standing order in the city, which -- (applause) -- we strongly believe that everyone should save a life; that it’s not just first responders -- which is very important. We actually started training our police as well. And within six months, our police officers have saved the lives of 21 citizens. (Applause.) So that’s very important.

But we also believe that if it’s true that addiction does not discriminate -- and it does not -- if it’s true that anyone can die from overdose -- and I’ve treated two-year-olds who have accidentally taken their parents’ medications, I’ve treated 75- year-olds who are on prescription drugs -- I mean, if it’s true that any of this disease can affect everyone, then we should all be able to save a life.

And so I issued the standing order. And now anyone who takes a very short training -- they can get training at a street corner, public market, public housing, in jails -- if they do a short training, they can get a prescription in my name. So 620,000 residents of our city have access to Naloxone. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: That’s what a solution looks like.

Mr. President, Dr. Wen brought up this point, and I think it’s an interesting one. It’s this idea that if you provide Narcan, Naloxone, more widely, do people feel like, look, I’ve got a safety net now, I may be more likely to continue using heroin, for example? Syringe service programs -- are they more likely to enable or foster continued usage of these drugs? Do these discussions come up as part of trying to pass some of these recommendations?

THE PRESIDENT: These discussions come up. The good news I think is that we base our guidance and our policy on science. (Applause.) And when you look at the science, there’s no evidence that because of a syringe exchange program or Naloxone, that that is thereby an incentive for people to get addicted to drugs. That’s not the dynamic that’s taking place.

This is a straightforward proposition: How do we save lives once people are addicted so that they have a chance to recover? It doesn’t do us much good to talk about recovery after folks are dead. And if we can save a life when they are in medical crisis, then we now are in a position to make sure that they can also recover so long as the treatment programs are available.

And I think what Leana said with respect to our populations in prison and the lack of systematic programming for them and support when they get out is a critical issue. Because if somebody has gone to jail for a nonviolent drug offense, and they are not getting treated and provided with some baseline of skills and some hand-holding when they are released, they are going to get back into trouble. That’s just human nature. And if we’re being smart on crime, and not just thinking in terms of sound bites, then this is going to be an area where we provide more resources. And the Department of Justice is working very closely with our Office of Drug Policy to find ways that we can improve

-- at the federal level -- reentry programs, drug treatment, and so forth.

Now, keep in mind that the vast majority of the criminal justice system is a state-based justice system. The federal government is not responsible for the majority of drug laws, the majority of incarcerations, or how the reentry works upon release. What we are hoping, though, is if we model best practices based on evidence, that more and more states will adopt it. And there’s an incentive for states to start doing so, and that is cost. If you can reduce the amount of recidivism, then you are saving money. If an individual -- like that young man I met in Camden who was in prison for drug offenses -- comes out, gets treatment, gets support, and gets training, and is now an EMT for the state of New Jersey, that’s -- (applause) -- and now is paying taxes and supporting himself and potentially supporting a family, that’s good for everybody. But that requires a certain amount of foresight in terms of how we’re approaching this problem generally.

The same is true, by the way, preventing people from getting addicted in the first place. (Applause.) I don’t want to -- as we’re, properly, talking about recovery -- because we’ve heard powerful stories from Crystal and Justin, and they’re inspirations for people who are watching, and I could not be prouder of them sharing their stories -- what we also want to make sure of is, is that a 3rd-grader has support that doesn’t make him feel the need to engage in this kind of more destructive behavior. (Applause.)

And that is something -- we’ve got two doctors in this panel so maybe they can address it. But as a layperson who’s studied this, we have a health care system that too often is really a disease-care system. We wait until people get sick and then we treat them. (Applause.) And we don’t spend enough time thinking about how do we keep people well and healthy and balanced and centered in the first place.

And that requires I think a reimagining of how our health system works. Very specifically, when it comes to opioids, the training of doctors for pain and pain relief, and how they help their patients manage pain -- this is an area where I was shocked to learn how little time residents in medical schools were spending just trying to figure this stuff out. It is not emphasized. It’s not considered prestigious or trendy to think about how are you managing pain with your patients.

And the good news is part of this initiative that we’ve got moving, we got 60 medical schools who’ve signed up and who are announcing today that they are going to make pain relief a major part of their curriculums, a major part of how they train their doctors -- (applause.)

DR. GUPTA: It’s really stunning, Mr. President. And I’ll tell you, it seemed like for a period of time -- and, Dr. Wen, you can share your experiences -- that pain relief was talked about a lot but only in the context of giving out drugs. The literature would all suggest, if you look back at those small reports, that there was no concern for addiction. And every single time someone came into an emergency room, even for a non-pain-related thing, they would be asked about pain and perhaps given narcotics.

Eighty percent of the world’s pain pills are consumed in the United States. We are 5 percent of the world’s population; we take 80 percent of the world’s pain pills. We don’t have 80 percent of the world’s pain -- my guess.

What do you think, Doctor Wen? How did we -- how did that happen?

DOCTOR WEN: I think two things happened. One is that drug companies very aggressively -- and I don’t know if it’s knowingly or not -- but they misled and marketed pain pills to physicians and patients. And we then developed this culture also of a pill for every pain. If I fall down and bruise my knee, I may not need opioids -- I’m sure I do not need opioids. But somehow we have said that our goal is to make people pain-free.

And so I’ve worked with many great doctors. I’ve trained with many fantastic people, including Doctor Murthy, our Surgeon General. And I know that doctors are trying to do the right thing. We’re not trying to get our patients addicted to medications. We’re not trying to get them to switch to heroin later. We need the resources to help us to then support us -- whether they are the guidelines as issued by the CDC, or whether they are other efforts by our medical societies to assist us, to make better decisions for our patients.

But we also need our patients and we need society to change, too. Because if I talk to one of our students in Baltimore City and I ask them, is heroin good or bad, they’re going to say heroin is bad. But if they see that every time that they’re acting out in class that they get diagnosed with Attention-Deficit Disorder, they get a pill, or if they see that their parents are in pain for -- maybe they sprained their back and they see their parents getting a whole month’s supply of Oxycodone -- I mean, this is the culture of excess that has to change. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: That’s a great point.

THE PRESIDENT: That is a great point. Sanjay, that’s what I mean about us reimagining how we think about health and wellness.

There’s a good analogy to this, and that is, in the whole field of antibiotics, where -- one of the things that we’re spending a lot of time with my team at NIH and CDC and FDA -- we have to worry about is the fact that antibiotics, which are one of the great breakthroughs of mankind and saves billions of lives because of their existence, are becoming less effective because every time somebody’s got a cold -- and I’ve been guilty about this as a parent. I don’t like seeing Malia or Sasha sick and so I go to the doc and I say, well, can’t we do something for her? And sometimes it’s just a cold, and an antibiotic is not going to work. But the over-prescription of antibiotics has led to increased resistance among the bacteria that need to be treated.

And so the doctor is right. We have to have a chance in the medical profession and the drug companies, and we have to hold them more accountable. We, as consumers and as parents, have to be more accountable, as well, in terms of how we approach keeping our families well in order for us to be able to prevent this massive gateway into addiction that can cause real problems.

DR. GUPTA: And I should point out, because you mentioned -- Dr. Frieden is here from the CDC. The CDC has released some of these new guidelines regarding opioid prescriptions saying that, look, pretty plainly stated -- I listened to you closely -- saying that these opiates should not be a first-line treatment for chronic pain. And that’s not the way the medical culture has thought about this for some time. The FDA now talking about black-box warnings on these medications as well to say there is a risk of abuse, of addiction, and even death from these things. So there are some solutions, some things that are changing as a result.

One of the things you said, Mr. President, was this idea that the substance didn’t get its “claws” in you, is what you said.

And I want to ask you, Justin, about that. We know how everybody in this room feels about addiction as a brain disease, but that’s still a hotly contested topic. Outside of this room, people talk about the fact that, is this a choice? Is there a component of moral failure? All those things. Your experience, and also how do you counsel the people and -- young people in recovery, the organization?

MR. RILEY: I’m really glad you asked this question. So I’m certainly not, again, a doctor. My sister is the doctor. I’m not an expert. I study, just try to be fully aware of what’s going on everywhere with the different ways in which the claws thing happens and can relate to that personally. But what I really am, what I would consider myself an expert in is opportunity and hope.

And so the question -- I’ll start with one of the statements that you said, Mr. President, which this is good for everybody. This isn’t like one of those things that we’re talking about that impacts a very small amount of people. And even if it was, that’s always good that we’re trying to help anybody that we can.

But since I’m not an expert when it comes to disease, not a “disease,” “choice,” “not a choice,” I really try to, and will here, publicly completely step aside from that conversation, because that isn’t my role or even our organization’s role to have that discussion from a medical perspective.

But what we will say, and the results that we have seen all over the country through our chapters and leaders all over, is that if given the opportunity -- and so this is something that I’m very excited to be able to share this, because this is something that I genuinely believe if you are or ever have been a person, you can relate to this -- is that whether you may have made some choices that you weren’t proud of, that maybe there were some choices and you said maybe I shouldn’t have done that, or maybe even something happened to you that was out of your -- duress, fear of control and influence, you can relate to the fact that, you know, if somebody just gave me a real shot at this and an opportunity -- I may not even know how I got to this situation or how these claws came here, whether somebody clawed into me or I even did this to myself -- but instead of focusing on that or being able to medically speak to that, I think the real opportunity is the opportunity -- I mean, that’s what this country is supposed to be about, right? Giving people an opportunity to get the resources and the tools that they need so they can and will and do recover all over the place. (Applause.)

THE PRESIDENT: Just to pick up on what Justin said -- as I said, I was lucky. I don’t know why. Friends of mine who ended up battling addiction were not less worthy or more morally suspect than I was. For whatever reason, things broke that way. But I think Justin’s point is correct, which is regardless of how individuals get into these situations -- and we don’t know everything. There may end up being genetic components to how susceptible you are to addiction, and addictions may be different for different people. What we do know is that there are steps that can be taken that will help people battle through addiction and get on to the other side, and right now that’s under-resourced.

And what we also know is that there are steps that we as a society could take that would help young people adjust and adapt to a rapidly changing and sometimes confusing world in a way that’s healthier rather than more destructive.

And it is affecting everybody. We do know that if you are poor, you’re more vulnerable. You don’t have the same antibodies to protect yourself. You don’t get the same second chances. And so part of the goal, hopefully, coming out of this conference is, is that because opioids affect everyone, but speak to a broader issue of how do we treat addiction generally, that we as a society, as a whole, are paying attention to what’s going on in our own kids’ lives, but we’re also paying attention to children who have a lot less resources than you or my children do.

Because, lo and behold, it turns out that if there’s a market for heroin in an inner city in Baltimore, it’s not going to take that long before those drugs find their way to a wealthy suburb outside of Baltimore. And I now have kids in high school and I am well aware that their access to -- their ability to access legal or illegal substances is very high. They are just less likely to get in trouble, get thrown in jail, and have a permanent felony record than the kids who live in those inner cities. (Applause.)

But again, to use the analogy, we care a lot about making sure no children in America have tuberculosis, because if a child has tuberculosis and is poor, at some point, they can give my child, who’s well-to-do, tuberculosis. And the same is true for addiction. It has an impact that can run through society as a whole, and that’s what we’ve got to pay attention to. (Applause.)

MR. RILEY: I think you’re -- obviously you’re absolutely correct. (Laughter.) But truly, though, I mean -- right? (Laughter.)

THE PRESIDENT: Let me just say that I am in Washington, D.C., and that is rarely said to me. (Laughter and applause.) Hal Rogers, I just want you to take note. (Laughter.)

MR. RILEY: So to continue to put a bow on the correctness, if you will, is, you know what -- again, you are absolutely correct. What I’ve also found, though, is that it’s even more, though. I used to think -- and even I think my family went through, well, what do we do? Tell me what to do for him. If we did this or if we did that, will the result change? And where we’re at with what we do know and what the experts are telling us is that it’s not an either/or solution here. This is an all. It is time for the country to go all in on this -- that this isn’t just simply just prevention or treatment or recovery, but it is everything. (Applause.)

And it is -- I mean, for us, the way that we talk about -- you asked, which is why I wanted to pipe back in, right -- is that what do we do with our members? I mean, what are we doing that is so exceptionally, extraordinarily different than other places? And it’s because we’re empowering them and we are equipping them.

I was asked for the briefing before all this stuff, what’s that thing that changed for you? Because I was given great opportunities. I was given amazing, different types of programs and treatment. But it was in a single moment in time when somebody look eyeball-to-eyeball with me and said, you have value; that regardless of maybe some of the choices you made, whether you put those claws there, whether somebody else did, is that you have value. And one day, you've got a lot to learn and you've got to listen and stop talking so fast -- (laughter) -- but you've got to focus up, and you have to know that you have value so you can give other people hope and help equip them and empower them.

And the way that we do that is through employment, housing, education, and other recovery-related resources. And those first three -- that is not unique to young people or even when I was even younger, right --or people of any age or of any recovery pathway. Those are things that individuals -- all individuals in this country need.

And when we start to have that conversation, that's how we go all in, and we support adequate recovery resources and employment, housing, and educational resources. We can do this thing together. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: I'm so glad you said that, because this is a multidimensional issue and we have to address all these things.

I want to ask almost about the next step. And this is s a story, Mr. President, I know is very personal to you -- the story of Jessica Grubb. Somebody goes in, they've gone through recovery now, they're in recovery, and they go in the hospital for something unrelated, and they're given a prescription for narcotics, for opiates again. They tell the doctors, look, I'm a drug addict, I cannot take this stuff -- if I do, I'll be right back on the road to addiction again and I could even die. That is what happened with Jessica Grubb. Mr. President, the stigma exists at all levels, even within the medical establishment -- after someone has been treated, someone is in recovery, even then, eh, you'll be fine, I'll still give you these opiate pain medications.

THE PRESIDENT: Well, this is where the training of the medical community comes in. There's been some controversy in this discussion around making this education mandatory, and I think the medical community worries about their independence over regulation of the medical communities. We have been getting some good volunteer efforts going, and I applaud those. We have to see how good the take-up is, because if, in fact, the training is not sufficient, then we may have to take a look at the possibilities of mandatory training.

I will tell you that within the federal government, for example, we have said, if you're going to treat somebody who is a federal employee or part of the federal health insurance program, you need to get trained. And so far, I think we have about 75 percent of the medical community that treats federal employees. I was able to do that through an executive action.

But I'd just go back to Crystal's point. I don't want Crystal -- if she is ready to get treatment and to do right by her kids, I want somebody who is fully supportive who she is interacting with on day one. I don't want somebody who has got an attitude. I don't want somebody who is misinformed. I don't want somebody who is not familiar with the best options that are available. I want somebody who is going to embrace her and say, let's go, let's see what we can do for you.

And I want to make sure that those doctors -- and perhaps nurses as well -- because in some communities, there aren't going to be enough doctors, and one of the issues that we have to address is, can we use -- and I just happen to love nurses as a general rule -- (applause) -- because they are overworked, underpaid, and are really just the foundation for so much of our health care system. But all the providers, I want to make sure that they're getting the resources and the reimbursements through whether it's third-party insurance, or Medicaid, or Medicare, in order for them to be able to do right by Crystal.

Because it's hard. And when somebody is ready to make that change, I want somebody to be right there with them, welcoming them -- not turning them away. (Applause.)

DR. WEN: And, Mr. President, I would also add that we need people like Crystal and Justin and other people in recovery working, as well, and, specifically, working with individuals with addiction. In Baltimore -- so I'm very proud to represent the Baltimore City Health Department, and on behalf of our mayor, Mayor Rawlings-Blake, as well, who really care about addiction as a public health issue. And we have individuals in our health department working at 24 needle-exchange sites across the city. Which, our needle-exchange program -- I'll tell you one statistic that continues to really surprise me, but also this is why we do the work that we do -- the percentage of individuals with HIV from IV drug use has decreased from 64 percent in 2000 to 8 percent in 2014. (Applause.)

And these individuals who work in our needle-exchange vans, most of them are in long-term recovery themselves. And for them to say to people coming -- to their clients and patients coming that you should think about quitting, and this is what we can do, we can help you with it, we can guide you through -- that's so much more powerful than me as a doctor saying to someone that recovery is possible.

And we do the same thing when it comes to violence prevention as well. We also believe that violence, just like addiction, just like other diseases, can spread. So we have a program in our city called Safe Streets -- that actually came from Chicago -- from Chicago's Cure Violence program -- where we hire individuals who were recently incarcerated, who were recently released from incarceration to walk the streets of Baltimore and interrupt violence. And these people are true heroes, and we need to find a way to reimburse and pay for peer-recovery specialists, who are the most credible messengers, who have walked in the shoes. (Applause.)

MR. RILEY: You're also 100 percent correct. (Laughter.) But really we've seen -- that excitement, that person that you described, Mr. President, that when they're ready to get help, I mean, imagine them meeting me. If I can't encourage you, your encourager is broken. You meet me on your day of need and help and you meet other young people and other people who are in recovery that have walked that journey -- who better to do that along with other professionals?

Again, it's not either-or. It isn't just simply now only fund peers. It is also fund massive and massive amounts of them. And one of our recent success stories is we said a long time ago -- and, again, I'm going to go back to that blunt thing -- is we decided to say we're just going to put our money where our mouth is and we're going to be the solution, in the meantime, until all these policies change.

And so what our chapter leaders and members have been doing is they've been providing those direct services and hosting our recovery support meetings, helping build recovery schools, collegiate recovery communities. And that action has been able to attract enough attention, because we're doing it, we're not waiting for things to change. Our amazing leaders are literally changing the communities, regardless of buy-in stigma, buy-in straight out discrimination against our own population.

But what has happened is even big insurance companies and other providers have come up and said, we will literally even pay you to further build out your own infrastructure, to put chapters around our communities. And this is a win-win. Again, this is good for everybody. So now big insurance says, we're going to pay you to go do what you were already going to do anyway. It helps the people in recovery. It helps the people that need recovery. And we're saving a ton of money -- not like Geico -- but, like, insurance because we're making sure that we're getting the money and the cost savings back because they're not going through that system again and again and again.

If we equip and empower, and not handcuff and jail people that are not well, and we focus on their wellness, that's part of the change. (Applause.)

DR. GUPTA: Pardon me, Mr. President. There's a lot of things that were announced today that are going to be part of this $1.1 billion that are spent. Is there a way to describe -- now that you've heard Crystal's story, for example -- a way to describe how her life will change, or a future Crystal's life would be different?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, first of all, the $1.1 billion is not yet allocated by Congress. So I want to be very clear about that. We've been able to reallocate some existing dollars for, for example, the community health centers. But this is still an area that's grossly under-resourced. So we're going to have to work with Congressman Rogers and other members of Congress to support policies that they've already embraced that's already reflected in legislation. But the way Congress works, sometimes they'll say this is a good idea, but until the money comes through, it's just that -- just an idea. It doesn't actually get done.

Crystal, remind me where you live. Where were you during this time where you entered into recovery?

MS. OERTLE: In Ohio. I live in Shelby, Ohio.

THE PRESIDENT: Is it more of a rural area?

MS. OERTLE: Where I live is, yeah.

THE PRESIDENT: I mean, one of the ways I would hope it would change -- and I don't know how easy or difficult it was for you to identify when you were ready to really make a change, where you could get treatment, and how long the waits were -- but I think the most basic thing that I'd like to see is that there is greater coverage of terrific programs like Justin is describing, good work that's being done by Leana in Baltimore. I want to make sure that there's sufficient coverage everywhere.

Part of what is troubling about the opioids epidemic is that we're seeing significantly higher spikes in rural areas. And part of that is because there has been a lot of under-resourcing of treatment facilities, mental health facilities. There may be, in some of those cases, more stigma than there might be in big cities about getting help. If you're in a small town, everybody kind of knows you -- you may be more hesitant, right? I don't know if that's an experience that you felt.

MS. OERTLE: Yes, definitely.

THE PRESIDENT: If you're in Manhattan, and you're going to get treatment, people are more -- may be more familiar with it. So part of what I think our goal is, is to make sure that we have, in counties all across the country, at least some resources that can get things started. Because as great as the work that Justin is doing, volunteer organizations are not going to be able to do it all.

And I want to emphasize -- there's wonderful work being done by the nonprofit sector and the philanthropic center, and we applaud that. For some, a faith-based approach is going to be critical to being able to get the wherewithal and the courage to be able to get through this thing. And obviously, traditional recovery programs have emphasized a higher power, and so there are a lot of -- great work that’s being done in churches and synagogues and temples and mosques all across the country on this issue. Say, you got an amen? (Laughter and applause.)

But ultimately, if we’re going to get coverage everywhere, then we’ve got to have government help. Community health centers are a very efficient way to do it, but there are -- we have to make sure that local hospitals, individual providers, insurance companies, Medicaid expansion are all part of this as well.

And this takes me back to why I pushed so hard for the Affordable Care Act. I know it’s been controversial. I understand. I understand the politics of it. But the main goal is to make sure that if you don’t have health insurance on your job -- which 85 percent of the American people do -- but at any given time, somebody who might previously have had health insurance on the job lost their job, or are between jobs, or are going back to school, or are starting a small business -- that in those circumstances, you’ve got some access to prevention; you’ve got some access to doctors; you’ve got some access to treatment if you end up being addicted. You have the ability if you’ve got some pain not to just rely on a one-time bottle of pills, but a doctor who knows your health history and is working with you, and can take you aside and say, you know what, Crystal, I’ve known you since you were X, or I helped deliver your baby, and let me just give you some advice here. I really think that you’re going to be better off, even though it’s going to be a little tough going through rehab on your shoulder, as opposed to taking a pill -- you’ve got to have a relationship with a wellness system.

And the problem is there’s still a lot of gaps, especially in rural communities, where that doesn’t exist. Even within the VA system, which has coverage all across the country. Typically, some of the biggest problems we have with the VA is in rural areas, where you’ve got to drive two hours or three hours to get treatment for any kind of medical problem. And it discourages people from using it. They start feeling isolated and they start self-medicating. And we see a lot of our veterans coming back self-medicating because they’re not -- they don’t have easily accessible treatment facilities.

Money is not the entire issue. Very rarely is money the solution alone. There’s got to be passion that Justin displays. There’s got to be the stories that Crystal shares. There’s got to be great dedication and professionalism like Leana. But money helps. (Laughter.) And without it, without the government, without us, collectively, as a society, making this commitment, what we will repeatedly end up with is being penny wise and pound foolish.

It is so much more expensive for us not to make these front-end investments, because we end up with jails full of folks who can’t function when they get out. We end up with people’s lives being shattered, folks not being as productive on the job, children then suffering from some of the problems of parents who are going through issues. That affects their schoolwork. That, in turn, has an impact on our economy as a whole.

It’s just smarter for us to do the right thing on the front end. And I hope that this conference will help underscore that. And I appreciate everybody’s great work in highlighting it.

DR. GUPTA: Mr. President, thank you very much.

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you so much. (Applause.)

END 3:46 P.M. EDT